As US-Sino Tensions Escalate, Post-Brexit Britain Must Definitively Choose a Side

When, on the 23rd June 2016 the BBC’s veteran political broadcaster David Dimbleby declared ‘we’re out‘, as the result of the the British-EU referendum, the economic and geopolitical landscape was one of flourishing world trade, established globalisation and apparently benign diplomatic relations between the the world’s only superpower and the twenty first century’s rapidly emerging counterpart, with Britain straddling the interstice.

Four years on and Britain has officially, if belatedly left the European Union, finally due to extricate itself from the trammels of transition on 31st December. The international situation however, has been drastically and detrimentally altered by the coronavirus pandemic.

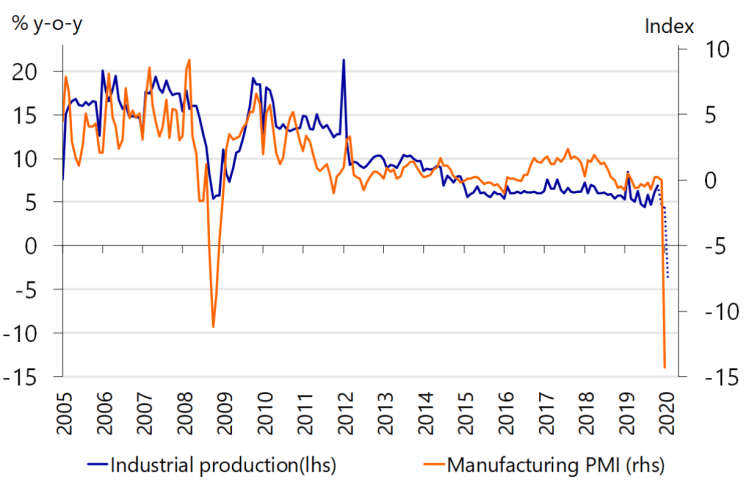

An exceptional worldwide health crisis, resultant collapse in global trade, contracting economic output, proliferating unemployment, spiralling sovereign debt and critically, extensive loss of human life has created a highly toxic mix, simultaneously eroding faith in international institutions and demanding a reappraisal of globalisation shibboleths.

Unprecedented disruption to trade flows has focused minds on inherent weaknesses in the prevalent outsourcing model; supply-chain security now the absolute priority, the consequent proposals for re-shoring producing myriad potential ramifications, from diminished world trade and elevated production costs to capacity constraints and debt crises, all conceivably precipitating diplomatic dislocations.

Already simmering tensions between the Trump White House and China’s President Xi Jinping have escalated on numerous fronts, with accusation and counter allegation from corporate espionage to clandestine laboratory ‘leaks‘ a virtually diurnal occurrence. China’s imposition of invasive new security laws upon Hong Kong, in breach of the 1997 British-Sino Joint Declaration, has become a proxy for the diametrically-opposed world views of the United states and China.

US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo declared Hong Kong ‘no longer autonomous from China‘, a move further increasing tensions between Washington and Beijing, potentially paving the way for a significant U.S policy shift toward Hong Kong (revocation of special status) which could have dire consequences not only for the enclave, but for the already vitiated global economy.

China’s response was rapid; Foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian declared Beijing ready and willing to take ‘any necessary countermeasures‘. The course of confrontation crystallised.

With the world’s focus firmly fixed on pandemic induced pandemonium, China has moved to implement a strategic revolution first publicly advanced by Xi in 2013, when he warned the CCP to ‘prepare for long-term conflict with the West‘, vowing to defeat the liberal free-market system. He doubled down some two years later with a rallying cry for an all out struggle against ‘dangerous Western views and theories‘. Statements of rebuttal toward fellowship and globally established rules of conduct and governance now made manifest.

Xi Jinping has conspicuously concluded any economic value derived from Hong Kong’s position as Asia’s foremost financial centre and China’s access point to global finance, is secondary to imposing his autocratic will upon the ostensibly democratic territory.

The US administration, preempting the Chinese move by a matter of days (with informed foresight?) published a staggering document, The US Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China, which spells out its long-held belief that China has become a fundamentally hostile power under the leadership of Xi Jinping.

The White House report proclaims the end to a restrained attitude toward global rivals, undertaken in the vain hope ‘their inclusion in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into trustworthy partners… this premise has turned out to be false, as rival actors have used propaganda and other measures to try to discredit democracy‘. A pronouncement of a new cold war.

Any doubts as to the efficacy of such a stark appraisal may be alleviated by the following excerpts:

‘The United States rejects CCP attempts at false equivalency between rule of law and rule by law; between counter-terrorism and oppression; between representative governance and autocracy; and between market-based competition and state-directed mercantilism. The United States will continue to challenge Beijing’s propaganda and false narratives that distort the truth and attempt to demean American values and ideals‘.

‘The United States does not and will not accommodate Beijing’s actions that weaken a free, open, and rules-based international order. We will continue to refute the CCP’s narrative that the United States is in strategic retreat‘.

‘We do not cater to Beijing’s demands to create a proper ‘atmosphere’ or ‘conditions’ for dialogue. Likewise, the United States sees no value in engaging with Beijing for symbolism and pageantry; we instead demand tangible results and constructive outcomes. We acknowledge and respond in kind to Beijing’s transactional approach with timely incentives and costs, or credible threats thereof‘.

The US is unmistakably articulating its determination to halt the unfettered, threatening rise of China.

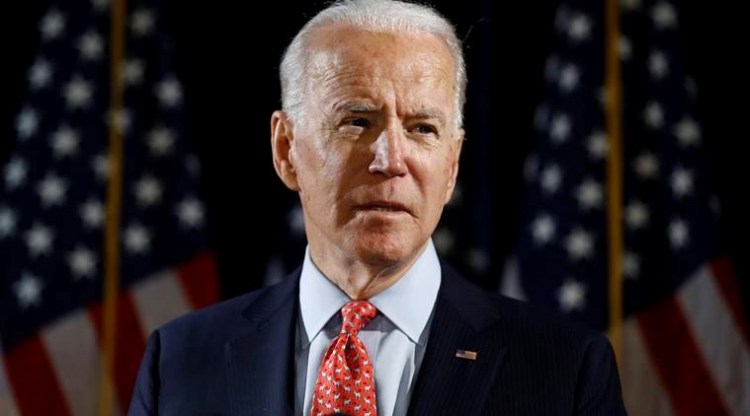

Should the November Presidential election effectuate a change of incumbent, the official position is unlikely to undergo significant attenuation, as the document represents the collective Washington perspective. Both parties on Capitol Hill, on this issue at least, speak with one voice. Indeed, a Biden Presidency could herald an even more trenchant approach, as the one time proponent of the ‘engagement with China doctrine‘ now propounds a more assertive stance, as the Democratic Presidential Candidate, toward Xi Jinping’s China. In a recent Presidential Primary, Biden indignantly described Xi as a ‘thug‘ who ‘has a million Uighurs in reconstruction camps, meaning concentration camps‘. He also spoke censoriously of Xi’s handling of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, saying, ‘This is a guy who doesn’t have a democratic (small D) bone in his body’.

Whether Trump retains the Presidency or Biden is inaugurated the 46th President of the United States, Xi Jinping has made a momentous error in abandoning the British-Sino declaration, (in flagrant violation of an international treaty lodged at the United Nations) awakening the US colossus from its protracted diplomatic slumber.

At one fell swoop, Britain’s studied diplomatic funambulism has been rendered redundant, obliging Her Majesty’s Government to take a meaningful stand and convincingly champion the US response. In a bold step, Prime Minister Boris Johnson pledged to amend UK immigration rules and offer millions of Hong Kong people ‘a route to citizenship‘ if China imposes the threatened draconian security laws.

Mr Johnson said the UK would ‘have no choice‘ but to uphold its ties with the territory, confirming that if China passes the controversial law, people in Hong Kong who hold British National (Overseas) passports (BNO) will be allowed to come to the UK for 12 months without a visa. Currently they are allowed to come for six months.

‘If it proves necessary, the British government will take this step and take it willingly. Many people in Hong Kong fear their way of life, which China pledged to uphold, is under threat. If China proceeds to justify their fears, then Britain could not in good conscience shrug our shoulders and walk away; instead we will honour our obligations and provide an alternative‘.

Approximately 350,000 Hong Kong residents currently hold a BNO passport, but a further 2.6 million are theoretically eligible. The proposals, if adopted, would amount to one of the most consequential changes to the visa & immigration system in British history.

In another divisive policy area, Britain is currently the only Five Eyes partner to permit a role for Huawei in its 5G system. The other members regard Huawei involvement as a serious threat to national security. The British government’s decision to admit Huawei came after years of intense debate at home and abroad. Britain’s allies have looked on in alarm as a pillar of NATO and the rules-based international order pursues a course that could potentially undermine the security of both its data and the data shared by others.

Until now, the British government has been relatively unresponsive to these concerns, apparently prioritising Chinese investment. Given the dramatic elevation in tensions between the US and China and the concomitant chill in British-Sino diplomatic relations, a policy volte-face, indicating an approach more in lock-step with close Five Eyes allies will, in this writer’s opinion, soon follow.

Atop an already unprecedented health and economic crisis, the deterioration of the West’s relationship with China represents a further significant blow to hopes of an expeditious recovery.

Stephen Cherry. 3rd June 2020.