The EU Stands On the Cusp of a Momentous, Democratically Deficient Decision. Ultimately, Who Will Be Answerable to Whom?

At its nadir, the 2008 financial crisis threatened to tear the European Union asunder, yet the wealthier (Northern) nations determinedly resisted pleas to embrace collectivised debt. This time however, the coronavirus pandemic has proven so economically deleterious, it has induced EU leaders to contemplate an unprecedentedly significant response, one with far-reaching consequences hitherto considered politically untenable.

The European Commission, the EU’s executive branch, has perceived opportunity in a crisis, proposing a dual expansion of its remit in the guise of an economic recovery plan: the authority to borrow €750 billion and the power to levy its own taxation.

The proposal, which faces numerous potential impediments to adoption, requiring as it does approval from all 27 national governments and their respective parliaments, would if passed be the first in the EU’s convoluted history to sanction substantial levels of mutualized debt and a regime of quasi-federal taxation, affecting a consequential step toward a pan-European common budget.

Ratification would be a momentous act, endowing the unelected Commission with powers more closely resembling those of an elected federal government.

Long standing controversy surrounding the democratic legitimacy of the EU comes into sharp focus in light of these proposals, as the Commission is devoid of publicly elected officials, its president included. The European parliament stands alone as an oasis of democracy among an ocean of appointees, as it consists entirely of elected members (MEPs), but the executive branch has no direct-link to the elected chamber. Commissioners are instead proposed by member states, (theoretically taking account of EU election results) then presented to the parliament for approval as an implicit fait accompli. Thus, the Commission stands at a remove from public accountability, lacking any direct electoral mandate.

Commission President, Ursula von der Lyen, is a perfect case in point: At the conclusion of the candidate selection process to replace outgoing President Jean-Claude Junker, Frau von der Lyen (a renowned pro-Federalist) was the singular candidate accepted by the European Council. MEPs from across the political spectrum expressed their perturbation at the abandonment of the Spitzenkandidaten process, (which in principal ties the choice of President to the results of the European elections) and the complete absence of a field of alternative candidates (their own candidate proposals having been rejected by the Council). Von der Lyen required 374 votes to secure the necessary majority. After a secret ballot and having faced no competition, she scraped in with 383, a wafer-thin majority of 9. A resounding declaration of support for a fair, unfettered democratic process this was not.

Looming calamitous recession across Europe, particularly detrimental to Southern member states, has provided fertile ground for a proposal that would otherwise have antagonised the populists and nationalists who vehemently oppose the ever-expanding ambit of Brussels’ power. The compelling need for a meaningful response to the virus has however suppressed dissenting voices – for now at least.

The climate of economic cataclysm has fostered growing anti-EU sentiment in those Southern member states, most notably Italy, as the cost burden has fallen on individual nations. Those disproportionately effected by the pandemic have been able to deploy only limited resources in response to the unfolding health and economic crisis, a hindrance to recovery compounded by elevated risk premia demanded by capital markets; an injurious position both caused and exacerbated by membership of the Eurozone. Germany, by contrast has deployed more than €1 trillion to support its domestic economy.

In mitigation of these limitations, the ECB has been attempting to prop up the European economy by purchasing prodigious amounts of EU debt. However, in the aftermath of the recent German Constitutional Court ruling, declaring significant areas of such intervention to be effectively fiscal transference and thus illegal, the Central Bank’s ability to maintain this role has been curtailed.

Into this partial vacuum has stepped Commission President Ursula von der Lyen, with her Recovery Fund proposal and its contingent augmentation of power. A proposition which would change the architectural balance of the EU.

Italy and Spain are considered simply too big and too central to the European Union to be allowed to fail, a distinct possibility, given their spiralling debt dynamics. (Italy has the world’s seventh largest economy and fourth largest – rapidly deteriorating debt-to- GDP ratio).

To address this existential threat to the EU project, the Commission plan not only proposes a monumental enlargement of joint debt (fourteen times larger than the Commission’s current issuance), but two thirds of those borrowed funds should be distributed in the form of grants, in preference to loans.

In the theoretical case of full EU debt mutualisation, where for example Germany would assume the obligation of guaranteeing Italy’s national debt, Berlin would require a veto over Italian budgetary choices as the logical quid pro quo. Even under current extremis, such an abject surrender of national independence and the resultant opacity in democratic accountability is considered so unpalatable as to be a political and diplomatic impossibility.

The Von der Lyen proposal, in a classic EU ‘fudge‘, sidesteps many of the insoluble issues around mutualisation, by making the European Commission the guarantor of the propounded joint debt, in preference to individual nations shouldering the burden, a scenario historically vociferously resisted by Germany, in unison with other ‘frugal‘ Northern member states and now rendered legally antithetical by the Verfassungsgericht.

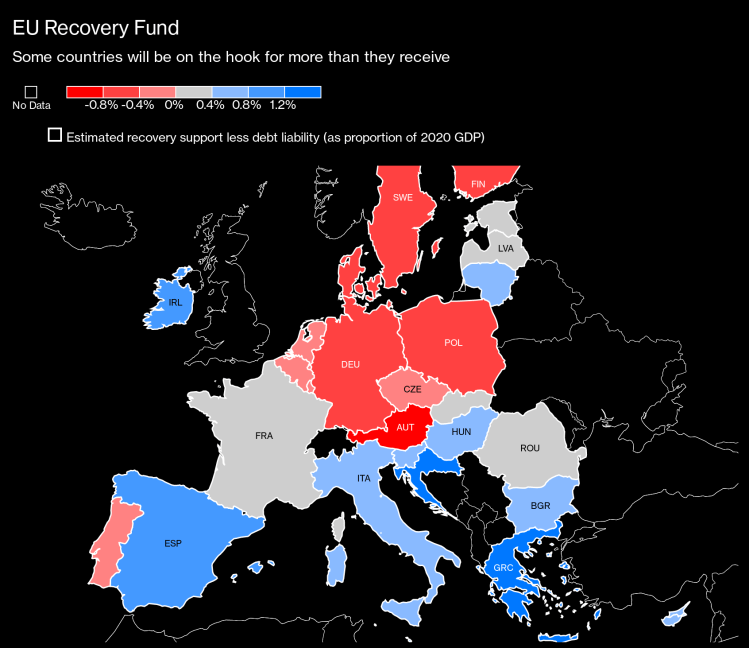

The crux of the matter however, is that the Commission acting as guarantor appears oxymoronic. The recovery fund is intended as a conduit for €500 billion of grants (alongside €250 billion of loan provision) to nations enfeebled by the pandemic. This presents as a fundamental flaw: as two thirds of the funds take the form of grants, they come with limited preconditions and no expectations of repayment. Unlike any comparable, elected ‘executive‘, the Commission is not self supporting, lacking any independent revenue stream, not permitted to run a deficit and thus without means of funding its proposed debt issuance. Ergo, the guarantee is a mirage. The reality once again is fiscal transference by legerdemain across EU member states, (see figure 1) for which there is no democratic mandate and doubtful legal authority.

Taxation, the second significant element of the Von der Lyen scheme may partially resolve the funding quandary, though with no insight into the level or scope of any tax regime, or the political viability of imposing such a supranational tax burden, the realistic potential is at best ambiguous.

Even assuming the relevant legislation were passed in all 27 member states and the tax receipts from this additional and doubtless unwelcome tax (enlarged tax burden detrimental to economic recovery) were sufficient to cover the funding costs of a gifted €500 billion (annual funding cost of €500 billion, accounting for amortisation over a 30 year curve, would require significant secure revenue), the recurrent issue of democratic legitimacy arises. The EU would need to address the same critical issue that originated the American War of Independence: ‘No Taxation Without Representation‘. The Commission would be attempting to impose a tax levy upon 430 million individuals with no direct democratic accountability. An indefensible position.

Failure to adopt a proposal resembling the Commission scheme will leave the Southern states trapped in the iniquitous Euro, unaided in fiscal purgatory. Adoption of such a plan would impose fiscal transference and pan-European tax burdens without democratic ascent.

The flaws at the epicentre of the European Union are laid bare by this conundrum. QED.

Stephen Cherry. 30th May 2020.