Just over a week ago, Germany and France pushed for another EU recovery fund, this time announcing a proposal to disperse €500 billion. Reports on the day suggested this was a boost for efforts to create a coordinated European fiscal response to the coronavirus pandemic. The fact estimated costs of relieving the crisis already stood at over €1 trillion went unaddressed.

German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president Emmanuel Macron revealed the initiative with a flourish via a joint video-conference, suggesting funds would be raised by the European Commission borrowing on capital markets, (a process only currently undertaken on a modest scale), and used to facilitate grants to struggling EU member states, as opposed to prevailing loans to national governments – more of which later.

The announcement was initially greeted favourably by bond investors, who perceived a potential mitigation to restraints upon the ECB’s bond buying programme, prompting a narrowing of spreads between Southern European bonds and the German benchmark.

Hyperbole abounded: Frau Merkel said the EU was facing the “gravest crisis in its history, and such a crisis demands appropriate answers”. Monsieur Macron described the proposals as “a major step”, going on to say “This is the transfer of real budget money to the worst affected regions and the worst hit sectors.” A rather blatant elision of theory and fact.

Bruno Le Maire, the French finance minister, added to the purple prose, hailing the initiative as “an historic step for France and Germany”, adding “It’s also an historic step for the European Union, because it’s the first time Germany and France stand together to have funding through debt of new investments for the EU countries.”

Not to be overshadowed, Olaf Scholz, Germany’s finance minister entered the fray, quoted as saying the EU was approaching its “Hamilton moment”, referencing the first US Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, who in 1790 created a US fiscal union by converting state debt to federal debt. He, like so many others, appeared to overlook the German Constitutional Court ruling (Verfassungsgericht), which declared such a profound step illegal under German law. (see ‘The Slow Fuse of Euro Destruction is Burning’. Broad-spectrum.org 10th May 2020).

To finance the plan, the two leaders advocated the expansion of the EU budgetary framework, “boosting a front-loaded MFF in the first years,” (Multi-annual Financial Framework), in combination with the European Commission borrowing on behalf of the EU.

The proposal called for a “swift agreement” on both the MFF and the Recovery Fund, describing it as “necessary to address the major EU challenges.” An exemplary expression of hope over experience.

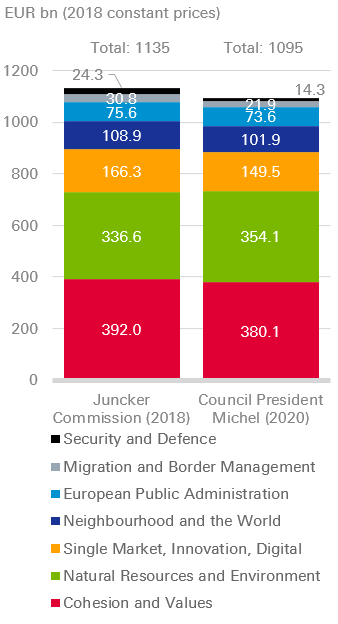

Here then, the very basis of the plan begins to unravel. EU budget negotiations continue to be mired in controversy. The current budget proposal, first presented in 2018, remains €1,000 billion, a figure adjudged sufficient for a seven year budget cycle prior to the pandemic. Reaching agreement has been further complicated by a demand for increased aid funding of €100 billion to guarantee the ‘SURE’ programme (Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risk in an Emergency), announced unfunded by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in April.

European Council president Charles Michel is responsible for brokering the illusive budget consensus at a yet to be scheduled summit. Finally securing agreement on a presently unspecified budget figure remains a highly complex and unpredictable process, given the antithetical opinions and long-term equivocation of member states during more than two years of wrangling.

Frau Merkel acknowledged that agreement was far from assured, saying “we are making a proposal, I think it will help to reach consensus in the EU-27, but we can’t force anyone”.

Merkel went on to say the European Commission would raise funds on the market “which we would then spend in the short term, but pay back over the long term”. She emphasised the funds would be distributed as grants not loans. “In terms of how this money is used, it is obvious that the countries worst affected by the crisis are those that will profit most from these funds”. Alternatively described as the countries least able to repay the funds will be in receipt of the most largesse.

The Franco-German plan requires either a significant enlargement of the demonstrably problematic MMF, a pronounced expansion in EU debt issuance via the Commission, or a weighted combination.

The EU Commission attracts credit ratings of AAA, Aaa and AA from Fitch, Moody’s and S&P respectively, on the basis EU borrowing may not be used to finance a budget deficit, the budget does not assume interest rate or foreign exchange risk and critically, borrowing is only permitted to finance loans to countries.

The EU has approximately €52 billion in outstanding debt instruments, funding the current alphabet soup of aid programmes: EFSM, BoP and MFA (excluding the ‘SURE’ proposals) and has a liquid yield curve consisting of 18 benchmarks.

Achieving agreement to a minimum 50% enlargement of the already deadlocked budget to finance the Merkel/Macron proposal looks a very distant prospect.

Relying on a prodigious expansion of EU Commission debt to fund the plan would be contingent on several considerably doubtful assumptions:

1. An unprecedented ten-fold expansion of existing issuance over a condensed time-frame.

2. Attracting sufficient market participation during a world-wide explosion in debt issuance, when ECB debt purchasing is constrained.

3. Issuing potentially non-repayable grants in direct contravention of the requirement to disperse funding via loans, repayable by the recipient member state.

4. Maintaining current credit ratings (and implied funding rates) having contravened the basis of current EU Commission borrowing.

5. Presumption this particular version of implied fiscal transference will be deemed either palatable or legal.

This latest proposal follows a litany of grande schemes designed to relieve the pressures inherent in the European project, all of which have been doomed to failure in addressing the fundamental flaws at the epicentre of the Eurozone:

Southern member states’ inability to issue debt in their in own currency, trapped in a system which deprives them of any flexibility to independently tackle persistent economic contraction.

The lack of Eurozone fiscal cohesion. The resolution to which is an undemocratic pooling of sovereign debt, seemingly rendered impossible by the German Constitutional Court. (The term sovereign debt, when applied to Eurozone members must be considered ambiguous, given no EZ member state is able to issue debt in their own independent currency, over which they have control of the money supply).

Enacting this latest ‘Recovery Fund’ would indubitably involve an unedifying display of national procrastination and potentially a raft of new legal challenges, given it involves yet another attempt at implicit fiscal transfer by legerdemain.

This writer is decidedly dubious the proposals will ever be ratified or implemented in anything like their current scale or form, which leaves Southern European bonds very exposed. Renewed spikes in volatility and yields are a distinct possibility, doubtless favouring German paper in a recommencement of flight to quality flows.

Risk/reward, positioning for another blow-out in Eurozone bond spreads looks like a sensible strategy.

Stephen Cherry. 26th May 2020.