Marvelling as stock markets recover from their precipitous declines, swiftly regaining ‘Bull Market’ status, while reading prognostications of economic ‘bounce back’ and returning normality, one is overwhelmed by incredulity.

Myriad challenges lay before us, from the unprecedented endeavour of restarting an economy rendered moribund by government dictum, to resuming mass public transportation and convincing returning passengers that safety claims are efficacious.

Private Consumption accounts for approximately 66% of UK GDP, making consumer spending a fundamental aspect of any presumed recovery. When considering this, and the pre-pandemic fragility of personal finances in Britain, the proposition of robust economic recovery appears incongruous.

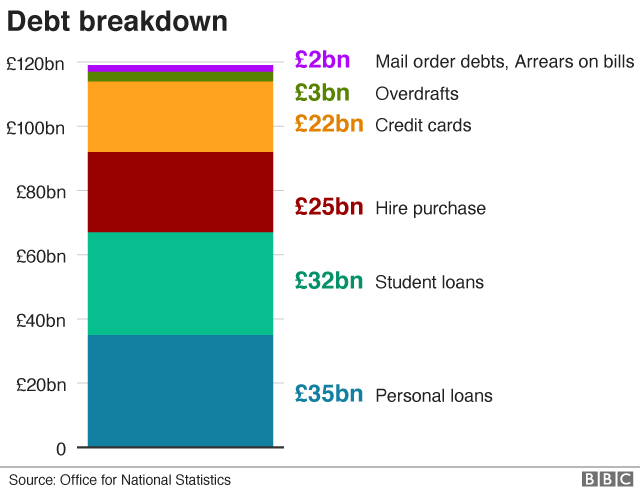

More than a decade of wage stagnation, base rate suppression and easy credit has resulted in the personal savings rate languishing near record lows, and personal borrowing spiralling to almost £120billion, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Average household debt, excluding mortgage borrowing stands just below £10,000, while a recent FCA study suggests 4.1m people are in serious financial difficulty.

Seven weeks into lockdown and the wages of a staggering 6.3million workers are being paid by the government’s furlough scheme. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates the originally envisaged period of three months will cost over £40bln, a figure equal to NHS spending on an annualised basis. Despite Chancellor Rishi Sunak offering assurances of “no cliff edge” to the job retention scheme, the prodigious costs render the scheme “clearly not sustainable”. Analysis conducted for the Daily Telegraph found that half of the adult population is now on the government payroll (6.3m on the retention scheme, 3m now claiming unemployment benefits, 5.4m public sector workers and 12.6m people receiving a state pension).

Former Bank of England MPC member David ‘Danny’ Blanchflower and Prof David Bell recently authored a report on the economic implications of the Covid 19 pandemic for the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR), in which they reach some startling conclusions: given the indeterminate length of the crisis, they estimate unemployment will rise from a pre-crisis 1.34million to over 6million, taking the unemployment rate to around 21%. They posit the UK is already in a depression, with the economic destruction making the 2008 recession comparatively ‘trivial’.

Eventually, the economy will emerge from its enforced hibernation, but the prospect of pent up demand delivering a significant consumer lead revival appears remote. Any improvement in consumption expenditure will, in this writer’s opinion be restricted not only by lingering concerns in relation to the transmission of Covid 19, but by that neglected truism, the paradox of thrift. Given de minimis personal savings, millions in the UK were estimated to be less than a fortnight from potential bankruptcy prior to the lockdown, a situation sure to be compounded by a sharp rise in joblessness. An imperative to create a savings buffer will logically trump any desire to return to the high street, as discretionary spending is supplanted by the need to ensure economic survival.

Recent market rallies do not appear to remotely account for the high probability of a deeply contractionary economic environment, investors assuming the white steed of government and central bank intervention will continue to underwrite indolent risk assessment. As the unwinding of lockdown restrictions are to be incremental and protracted, negative GDP data will likely persist over the coming quarters, growth restrained by depressed consumer confidence, elevated unemployment and a significant contraction of the productive base. When recovery materializes, it will be belated, anaemic and inconsistent. Further declines across all asset classes must be the corollary.

Stephen Cherry. 5th May 2020.

One thought on “Who Will Spearhead the Promised Recovery?”